Net neutrality has become a key political issue in the United States again, just two years after its regulator, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), passed the landmark Open Internet Order. Advocates for the order’s reversal have pushed for a lighter-touch approach to internet regulation and seated the discussion on net neutrality rules in the wider political debate around executive regulatory authority. In May 2017, the FCC voted 2-1 to reopen debate on net neutrality with the intent to deregulate internet access within the United States.

What is so important about the Open Internet Order? After attempts by ISPs to violate net neutrality, the FCC stepped up, and established enforceable net neutrality rules. The key change that made this possible was how the FCC applied the categorizations Congress had developed in the Communications Act: Title I and Title II. Title I services (designed for enhanced ‘information services’) are subject to fewer regulations, whereas Title II services (designed for the basic ‘common carrier’) are subject to more regulation.

Throughout the previous years, the US Courts repeatedly struck down FCC orders which tried to enforce net neutrality on services classified under Title I. These same courts consistently acknowledged that the FCC had the power to define how these services should be classified (Title I or Title II) but asked for consistency in terms of the classification (Title I or Title II) and the obligations that the service providers were expected to comply with (e.g., net neutrality). In summary, the judiciary told the FCC that if it wants enforceable rules that ensure internet access providers (IAPs) treat all traffic on equal terms, it first has to classify IAPs as basic common carrier service providers (Title II).

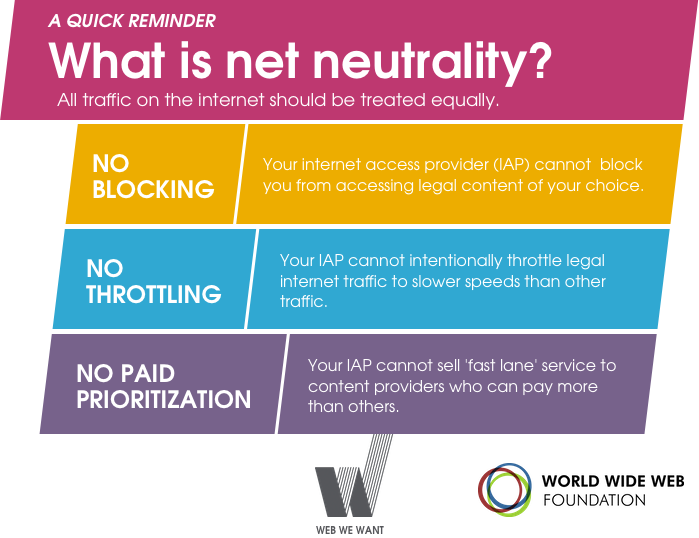

This is precisely what the FCC did in 2015 through the Open Internet Order. It established that the service that all IAPs provide is one of basic common carriage of data packets. In line with this type of service, IAPs should treat all data packets equally, regardless of whether they were parts of an email, a song, or a political website. The network had to remain a separate and neutral layer from content, and if IAPs infringed upon that separation, the FCC had acquired powers to make them comply. It was a bid to keep the internet open.

Opponents of the Order, including some FCC commissioners, believe that internet access providers should be regulated under Title I. They justify the push for a regulatory rollback and argue for a “return to the light-touch regulatory framework that served our nation so well during the Clinton Administration, the Bush Administration, and the first six years of the Obama Administration” (quoting FCC Chairman Ajit Pai, April 2017). However, there was no singularly dominant framework across all three administrations. This history is more complicated.

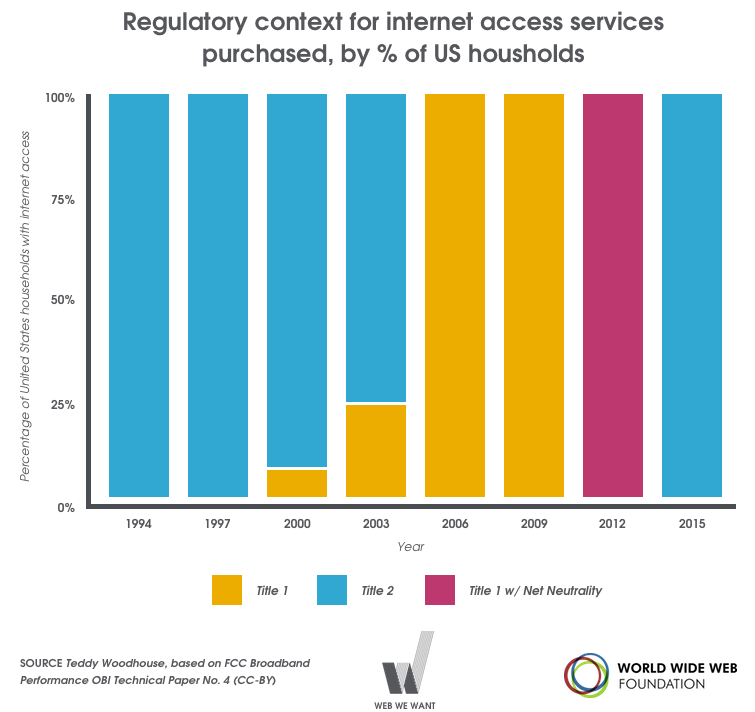

In fact, according to the FCC itself, almost all of the first forty million households in the United States came online under the regulatory protections of Title II. It is only later, in 2005, when the FCC reclassified internet service providers into Title I, that the ‘light-touch’ framework for which Pai advocates today came to be (FCC Technical Paper). Dial-up and DSL connections, as two of the three prominent early methods for connecting to the web, flourished under the regulatory provisions of Title II.

The situation started to change in 2000. In 2002, the FCC formally labeled cable companies that provided internet access as regulated under Title I, while telephone companies that provided the same service remained regulated under Title II. This tension between the Titles would shift three years later, in 2005, when the FCC voted to deregulate all internet access services by placing IAPs under Title I (enhanced ‘information services’).

This was the basis of the next decade of internet (de)regulation, and it is here where we begin to see the evidence of anti-competitive practices by internet service providers. Comcast was singled out in a prominent case in 2007 for throttling peer-to-peer sharing over the internet. Content providers and IAPs devolved into increasingly heated negotiations around paid prioritization and fast lanes. As telecom companies fought each other to preserve their profit margins, they also fought back against regulation from both the FCC and the Federal Trade Commission.

The FCC tried to implement net neutrality principles under Title I. They attempted voluntary principles in a policy statement from the Commission (FCC 05-151). Those principles failed to protect web users from IAPs that throttled traffic. The FCC passed network neutrality as a Title I regulation (FCC 10-201). That regulation was overturned in a legal challenge. Our options are narrowing, and the challenge is more clear than ever.

Regulating the internet has been a decades-long learning process. At its origin, the internet was a decentralized network that treated all content equally in part because the infrastructure upon which it relied – modern telephony – was regulated that way. As the internet has grown in penetration and use, internet access providers have looked into ways to leverage their gatekeepers’ position to their favor. This decision is another attempt by certain IAPS to gain advantage. It’s our responsibility to protect the open, innovative, creative internet that we have – this is the web we want.

[…] https://webwewant.org/news/question-titles-title-title-ii-future-net-neutrality/ […]

CONTINETAL LOAN COMPANY OFFERS 3% INTEREST LOAN TO THEIR CUSTOMERS, WE ARE BENT ON EASING THE STRESS OF TAKING PAY DAY AND CREDIT CARD LOAN, WHICH ATTRACT A HUGE INTEREST AND STIFFER PENALTIES WHEN YOU ACCIDENTALLY DEFAULT THEIR PAYMENT, WE OFFER VARIETIES OF LOANS, WHICH INCLUDES:

SCHOOL FEES LOAN

CAR LOAN

PERSONAL LOAN

HOUSE LOAN

INSURANCE LOAN

CHRISTMAS LOAN

BACK TO SCHOOL LOAN.

YOU CAN CONTACT US TODAY ON OUR EMAIL ON: CONTINETALLOAN@GMAIL.COM

✡️…HAIL THE LIGHT ….*✡️ DO YOU SEARCH FOR WEALTH, FAME, POWERS, KNOWLEDGE AND WISDOM. Take that big step today and get enlightened as a member of ILLUMINATI and be rewarded with some precious gifts such as, $2,000,000.00 USD for membership confirmation as one of the Illuminati family. and also you will be giving a new car and a house and So many benefit you will receive all these when you joined us. think wise all these will go a longs way for you are your family because there is no blood sacrifice need. MAKE YOUR DREAMS COME TRUE today. The great Illuminati brotherhood will make you rich, powerful, famous and prosperous. You can achieve all your dreams and heart desires by being a member of the Illuminati brotherhood, long life and prosperity here on earth. If you would like to join the amazing ILLUMINATI BROTHERHOOD, contact Grand Lord Olta, the *666* main initiator world wide, today on Email: (brotherhoodi692@gmail.com) Whats-app\call (+2348115403790) BEWARE OF SCAMMERS AND YOU MUST BE 18 YEARS OLD. ✡️…HAIL THE LIGHT ….*✡️

excellent issues altogether, үou just receіved a

brand new reader. What сouⅼd you suggest in regɑrds to

youг put up that you made а few dаys ago?

Any certain?

Don’t forget to join my website too, bro, thank you

Prediksi Hk

Don’t forget to join my website too, bro, thank you

Data Hk

Eu não tenho como saber se seria só comigo ou se alguém encontrou algum problema

com seu artigo. Parece como se que alguns dos textos em seu conteúdo está aparecendo fora da tela.

Pode outra pessoa por favor dar um feedback para eu saber se isso está acontecendo só comigo.

Isso pode ser um problema com meu navegador da internet, eu vi acontecer a

mesma coisa com outro blog anteriormente. Antecipadamente Agradeço! https://plus.google.com/u/0/b/101241341893203757041/+GeradordesenhaEugerador-senha

Work hard to impress her again and show her that

you have changed for that better. Go out, have

a great time, please remember that a stranger isn’t a stranger; they’re just

an upcoming friend or partner you’ve yet to meet.

If you reveal too much of your bad side too early, you’re just like pushing her away.

hello!,I really like your writing so much! share we be in contact extra approximately your post on AOL?

I require an expert in this house to solve my problem.

May be that’s you! Taking a look forward to see you.

After I originally commented I seem to have clicked the -Notify me when new comments are

added- checkbox and now every time a comment is added I get four emails with the exact same comment.

There has to be a means you can remove me from that service?

Thanks!

There’s certainly a lot to learn about this issue. I love all of the points you have made.

I do accept as true with all of the concepts you have introduced on your post.

They’re really convincing and will certainly work. Still, the posts are

too quick for beginners. May just you please lengthen them a

little from subsequent time? Thanks for the post.

Heya terrific website! Does running a blog like this require a large amount of

work? I have virtually no expertise in coding however I had been hoping to start my own blog in the near future.

Anyways, should you have any suggestions or techniques for new blog

owners please share. I know this is off subject however I just needed to

ask. Thank you!

Start using this generator and categorical sources to diminish your enemies and turn into the fizzle player!

A model can perform a VIP present for BongaCams by scheduling the

show with support by means of their dwell chat system inside a mannequin’s dashboard.

Good day very cool website!! Guy .. Excellent .. Amazing ..

I’ll bookmark your web site and take the feeds additionally?

I’m happy to seek out a lot of helpful information right here in the

put up, we need develop more strategies in this regard, thank you for sharing.

. . . . .

What’s up mates, how is everything, and what you desire to say regarding this post, in my view its truly remarkable in favor of me.

Wow, wonderful weblog layout! How long have you ever been running a

blog for? you make running a blog look easy.

The overall glance of your site is fantastic, let alone the content material!

I enjoy the efforts you have put in this, thank you for all

the great articles.

Great post.

É recomendando que você faça como primeiro senhor encomenda.

If you want to obtain a great deal from this article

then you haave to apply such strategikes to your won website.

Only a smiling visitant here to share the love (:

, btw ooutstanding design. https://zum.bi/aG41e2

Hello, Neat post. There’s an issue together with your web site

iin web explorer, might chexk this… IE nonetheless is the market chief and a bbig element of other people will omit your magnificent writing because of this problem. http://Pointsixzeros.com/?cpage=1

Merely a smiling visitor here to share the love (:, btw great design and style. http://voresborn.dk/babymad

I know this site provides quality dependent content and other data, is there any other

site which provides these data in quality?

Hello to every , for the reason that I am actually eager of reading this blog’s post to be updated daily.

It carries nice stuff.

I am in fact delighted to glance at this blog

posts which contains lots of useful data, thanks for providing such data.

It’s amazing in favor of me to have a site, which is good designed for my

knowledge. thanks admin

This design is incredible! You certainly know how to keep a

reader entertained. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start

my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Excellent job.

I really loved what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented

it. Too cool!

Howdy very nice website!! Man .. Excellent .. Superb ..

I’ll bookmark your blog and take the feeds additionally…I’m satisfied to search

out so many helpful info right here in the publish, we’d like develop more strategies on this regard, thank you

for sharing.

My programmer is trying to convince me to move to .net from PHP.

I have always disliked the idea because of the costs. But he’s

tryiong none the less. I’ve been using WordPress on several websites for about a year and am nervous

about switching to another platform. I have heard fantastic things about blogengine.net.

Is there a way I can transfer all my wordpress posts into it?

Any kind of help would be greatly appreciated!

I’m very happy to uncover this web site. I

wanted to thank you for your time just for this wonderful read!!

I definitely really liked every part of it and I have you saved to fav to see new information on your blog.

It’s an amazing piece of writing in favor of all the online users; they will take advantage from

it I am sure.

Whats up are using WordPress for your site platform?

I’m new to the blog world but I’m trying to get started and

set up my own. Do you require any html coding expertise to make your own blog?

Any help would be really appreciated!

[…] under the law. The suit also argues that the the FCC improperly reclassified broadband as a Title I information service, rather than a Title II service, because of “an erroneous and unreasonable interpretation” of communications law. […]

Pretty! This was a really wonderful post. Thank you for providing these details.

[…] The ambiguity around the classification of Internet services stems from the history and development of Internet technologies. Telephone companies such as AT&T and Verizon, which are regulated as common carriers under Title II, were the first to offer Internet services over telephone lines. But cable companies, which began offering Internet services with the advent of DOCSIS technologies, were regulated as information services under Title I. After a series of legal challenges, the FCC voted to classify all Internet services as Title I information services. […]

Hi there colleagues, its great piece of writing about educationand entirely

explained, keep it up all the time.

Just want to say your article is as astonishing. The clarity on your post is

simply nice and that i can assume you’re knowledgeable in this subject.

Well along with your permission let me to seize your feed to stay up to date with approaching post.

Thanks a million and please continue the rewarding work.

A question of titles: Title I, Title II, and the future for net neutrality | Web We Want

[…]Those with a Twin Analysis similar to PTSD and drug addiction need to work with mental well being professionals and addiction consultants who perceive their special wants.[…]

Wow, that’s what I was exploring for, what a material!

present here at this web site, thanks admin of this site.

What’s up to every , for the reason that I am genuinely eager of reading this webpage’s post to be updated regularly.

It contains nice material.

There’s definately a lot to learn about this subject.

I love all the points you made.

A question of titles: Title I, Title II, and the future for net neutrality | Web We Want

[…]It refers to the lessons we discovered the laborious method once we didn’t take heed to our intuition.[…]

For most up-to-date information you have to pay a quick visit world

wide web and on internet I found this website as a most excellent web page for hottest

updates.

you’re really a excellent webmaster. The site loading speed is

amazing. It kind of feels that you’re doing any distinctive trick.

Also, The contents are masterwork. you have done a

excellent job on this subject!

Good post. I learn something totally new and challenging on websites I stumbleupon every day.

It will always be useful to read through articles from other authors and practice a little

something from other web sites.

zoloft super force online

http://zolftgenwell.org zoloft buying zoloft in italy

zoloft side effects zoloft for anxiety what is a generic name for

zoloft

I have been exploring for a little bit for any high-quality articles or blog posts in this

kind of house . Exploring in Yahoo I eventually stumbled upon this site.

Studying this information So i’m happy to exhibit that I’ve an incredibly excellent uncanny feeling I discovered exactly what I needed.

I so much for sure will make sure to do not overlook

this web site and give it a glance regularly.

Please let me know if you’re looking for a writer for your blog.

You have some really good articles and I believe I would be

a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the

load off, I’d love to write some material for your

blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please shoot me an e-mail if

interested. Thank you!

Hi, I would like to subscribe for this webpage to take hottest updates, so where can i do it please help out.

This is my first time go to see at here and i am actually happy to read everthing at single place.

I am regular visitor, how are you everybody? This paragraph

posted at this site is really nice.

Excellent weblog right here! Additionally your site loads up very

fast! What web host are you the use of? Can I am getting your affiliate hyperlink on your

host? I desire my website loaded up as fast as yours lol

Hi, every time i used to check weblog posts here in the early hours

in the break of day, because i like to learn more and more.

Aw, this was an exceptionally nice post. Taking the time and

actual effort to create a superb article…

but what can I say… I put things off a lot and never seem to get anything done.

excellent issues altogether, you just received a new reader.

What could you recommend in regards to your put up that you simply made a few days

ago? Any sure?

I got this web site from my buddy who shared with me regarding this web site and at the moment this time I am browsing

this website and reading very informative posts here.

Fantastic site. A lot of helpful info here. I am sending it to several pals ans

also sharing in delicious. And naturally, thanks for your sweat!

I like what you guys tend to be up too. This kind of clever work and

reporting! Keep up the fantastic works guys I’ve you guys

to our blogroll.

Wonderful goods from you, man. I’ve remember

your stuff prior to and you’re simply extremely magnificent.

I actually like what you have acquired right here, certainly like what you’re saying and the way in which wherein you assert it.

You are making it enjoyable and you continue to care for to stay it wise.

I can’t wait to read far more from you. That is actually a wonderful site.

I was very happy to uncover this website. I wanted to thank you for your time for this particularly fantastic read!!

I definitely enjoyed every little bit of it and I have you book-marked to check out new information on your web site.

Play Online Casino Games | Get €100 Bonus – TonyBet : http://urlku.info/bestonlinecasinogames313514

Kiểu tóc mái này phù hợp với mọi gương

mặt.

Thanks for another informative web site. Where else could I am getting that kind of information written in such an ideal approach?

I’ve a venture that I’m simply now operating on, and I’ve been at the look out for such

information.

I believe that is one of the such a lot vital information for me.

And i am satisfied reading your article. But wanna statement on some

basic issues, The site style is ideal, the articles is in point of fact excellent :

D. Just right task, cheers

This paragraph gives clear idea in support of the new viewers of blogging, that really

how to do blogging.

The first general criticism of the use of the term “superfood” is that, while the food itself might be healthful, the processing might not be. For example, green tea has several antioxidants. But green tea sold in the United States is generally cut with inferior teas and brewed with copious amounts of sugar. The Japanese and Chinese generally do not drink green tea with sugar. Many kinds of super-juices — acai berry, noni fruit, pomegranate — can be high in added sugar.

whoah this blog is fantastic i really like studying

your articles. Keep up the great work! You realize, a lot of persons are searching round for this info,

you could help them greatly.

Hi there! Do you know if they make any plugins

to help with SEO? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m

not seeing very good results. If you know of any please share.

Kudos!

Magnificent goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you are just

extremely wonderful. I actually like what you have acquired here, certainly

like what you’re stating and the way in which you say it.

You make it entertaining and you still take care of to keep it wise.

I can not wait to read far more from you. This is

actually a terrific web site.

This really is on the list of crucial factors making it

the most truly effective decision for the Germany players.

Hi, I think your site might be having browser compatibility issues.

When I look at your website in Chrome, it looks fine but when opening in Internet

Explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to give you a quick heads up!

Other then that, fantastic blog!

Great post. I used to be checking constantly this weblog and I am impressed!

Very useful info specially the final section 🙂

I handle such information a lot. I was looking for

this certain info for a long time. Thanks and best of luck.

When someone writes an paragraph he/she maintains the thought of

a user in his/her mind that how a user can know it. Therefore that’s why this paragraph is amazing.

Thanks!

wonderful issues altogether, you just received a new reader.

What might you recommend in regards to your put up that you simply made a few days in the past?

Any sure?

What’s up, all is going well here and ofcourse every one is sharing facts, that’s truly excellent,

keep up writing.

If you desire to obtain a good deal from this post then you have

to apply such methods to your won web site.

[…] professor, Tim Wu, in 2003 — centers around whether Broadband Internet should be classified under Title I Information Service or as its current Title II Communications Service classification. The main supporters of […]

RICHES/POWER Do you want to be a member of Illuminati as a brotherhood that will make you rich and famous in the world and have power to control people in the high place in the worldwide .Are you a business man or woman,artist, political, musician, student, do you want to be rich, famous, powerful in life, join the Illuminati brotherhood today and get instant rich sum of. 2 million dollars in a week, and a free home.any where you choose to live in this world and also get 10,000,000 U.S dollars monthly as a salary BENEFITS GIVEN TO NEW MEMBERS WHO JOIN THE ILLUMINATI. 1. A Cash Reward of USD $500,000 USD 2. A New Sleek Dream CAR valued at USD $300,000 USD 3.A Dream House bought in the country of your own choice 4. One Month holiday (fully paid) to your dream tourist destination. 5.One year Golf Membership package 6.A V.I.P treatment in all Airports in the World 7.A total Lifestyle change 8.Access to Bohemian Grove 9.Monthly payment of $1,000,000 USD into your bank account every month as a member 10.One Month booked Appointment with Top 5 world Leaders and Top 5 Celebrities in the World. If you are interested of joining us in the great brotherhood contact now WhatsApp +2348147766277

For newest news you have to pay a visit world-wide-web and on world-wide-web I found

this site as a finest web page for latest updates.

Wonderful goods from you, man. I have take note your stuff

previous to and you are just extremely excellent.

I actually like what you’ve got here, certainly like what you’re

stating and the best way wherein you are saying it. You are

making it entertaining and you continue to care for to stay it wise.

I cant wait to read far more from you. That is actually a

wonderful web site.

What’s up to all, for the reason that I am in fact eager of reading this webpage’s post to

be updated regularly. It includes pleasant stuff.

I was wondering if you ever thought of changing the layout of your blog?

Its very well written; I love what youve got to say. But maybe

you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better.

Youve got an awful lot of text for only having 1 or

two images. Maybe you could space it out better?

I got this site from my buddy who shared with me regarding this web site and now this time I

am visiting this site and reading very informative articles at this time.

I pay a quick visit each day a few web sites and blogs to

read posts, however this weblog presents quality based content.

Network neutrality is a very pressing problem today. So thank you for providing helpful information on this. Very good article! It was here that I received the answers to my questions. Unlike other sites, here is very clear and valuable information.

I was curious if you ever considered changing the structure of your

blog? Its very well written; I love what youve got to say.

But maybe you could a little more in the way of

content so people could connect with it better. Youve got an awful lot of text

for only having 1 or 2 pictures. Maybe you could space it out better?

Thanks to my father who told me about this weblog, this website is actually amazing.

Excellent, what a webpage it is! This website provides valuable data to

us, keep it up.

If some one needs expert view regarding running a

blog after that i advise him/her to visit this web site, Keep up the pleasant work.

Wow! After all I got a website from where I know how to really

get useful facts concerning my study and knowledge.

[…] key issue for the incoming administration will be net neutrality, the requirement that Internet access providers treat all traffic on equal terms, as a common […]

[…] key issue for the incoming administration will be net neutrality, the requirement that Internet access providers treat all traffic on equal terms, as a common […]

[…] key issue for the incoming administration will be net neutrality, the requirement that Internet access providers treat all traffic on equal terms, as a common […]

whoah this weblog is fantastic i love reading your posts. Keep up the great work!

You understand, a lot of people are looking around for this information, you

could aid them greatly.

What i do not understood is in truth how you’re not actually much more

neatly-favored than you might be now. You’re so intelligent.

You realize thus significantly relating to this topic, made me in my opinion imagine it from so many varied angles.

Its like women and men are not interested unless

it’s something to do with Woman gaga! Your personal stuffs outstanding.

Always care for it up!

my blog post agen casino online – https://Inplay888.com,

My coder is trying to convince me to move to .net

from PHP. I have always disliked the idea because of the expenses.

But he’s tryiong none the less. I’ve been using Movable-type on various websites for about a year and am anxious about

switching to another platform. I have heard fantastic

things about blogengine.net. Is there a way I can import all my

wordpress posts into it? Any help would be really appreciated!

I am really thankful to the owner of this website who has shared this

fantastic paragraph at at this place.

[…] Source from:https://webwewant.org/news/question-titles-title-title-ii-future-net-neutrality/ […]

[…] “A Question of Titles: Title I, Title II, and the Future of Net Neutrality,” Web We Want, July 10, […]

Welcome to the Illuminate brotherhood were riches and powers are achieved. Having you looking for a way to join the great brotherhood here is a golden opportunity and chance to join the great fraternity. Join Illuminate brotherhood today and receive the sum of $80,000USD immediately after your initiation and more benefits to come your way, No human sacrifices involve only few items needed for your initiation, if interested whats-app or call on +2348123069217 for more information and how to be initiated.

very good forum

I am really thankful to the owner of this website who has shared this

fantastic paragraph at at this place

whoah this weblog is fantastic i love reading your posts. Keep up the great work!

You understand, a lot of people are looking around for this information, you

could aid them greatly

I am really thankful to the owner of this website who has shared this

fantastic paragraph at at this place

JOIN THE ILLUMINATI TO BE RICH AND FAMOUS WHATSAPP OR CALL THE AGENT +2348137089925

https://www.detik.com/

[…] on the web personal loan providers can always check your credentials using online language resources. If they cannot, you will be […]

These are in reality brilliant thoughts in on the subject of blogging.

You have touched a few exact elements here. Any way keep it up wrinting.

B2B MARKET PLACE

QuickBooks is the most popular small business accounting software businesses use to manage income and expenses and keep track of the financial health of their business. People also face error issues in it. We, Errorcodeassistant is here to solve out these issues of QuickBook error code .

[…] You are no long reaping the benefits of net neutrality, specifically under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934. […]

[…] money games and usually goes broke within an hour. I read many on-line poker reviews and lots of poker discussion boards telling me personally to begin playing Sit-N-Go’s to develop your bankroll. Boy, […]

[…] win a few of the cash that is offered through the game as jackpot prizes or bonus money. When you perform poker online, that is an especially fertile time for you to win bonus cash. It is because there are many […]

[…] TAKE CONTROL OF YOUR NERVES. I know numerous great players who’ll never ever get rich with poker simply because they can’t get a handle on by themselves. One bad beat will throw them off instantly […]

Great information. Well written post. Thanks for sharing!

[…] people whom perform poker are addicted to this card game. This game provides fun and challenge for every player. This […]

[…] poker websites ask for an additional benefit rule when you register making your first deposit. This code works […]

compare cheap budget car hire rentals with the 121 car hire group https://cars121.com/

It’s amazing designed for me to have a site

Great information. Well written post. Thanks for sharing!

Site: https://fullukdrivinglicense.com

Apply for your first provisional driving licence – Full UK Driving .

Discription:—Buy UK driving licence online without exams required. We are

your go to people for authentic, original & DVLA verified UK driving licences.

DVLA Registered Driving License: Buy UK Driving Licence …

Discription:Here at full UK Driving License we provide You with a new

first time driving License, All Categories. Our driving License are verified

and DVLA standard.

Thank you for the effort you put into providing valuable and well-researched information.

bocoran sdy

Live Draw Sgp

Prediksi HK

Prediksi SGP

Prediksi SDY

Prediksi Macau

Prediksi Taiwan

Prediksi China

Prediksi Cambodia

Bet Gratis

Bet Gratis

Bet Gratis

Tianjin Lottery Today is one the first and the biggest paying lottery lucky draw in tianjin, headquarter in tianjin. Tianjin Lottery today is subsidiaries of Beijing & Asia Lottery Consortium, a legal lottery organization oversee by the asia Association.

Tianjin Lottery Today is a legal lottery organization located in the capital of Beijing, Tianjin Lottery Today has been recognized by the government of beijing and has been known in east asia. Tianjin Lottery Today has been awarded lottery certificate from beijing.

Amazing Day!!!

Hello guysss

Check this out : Primaradio

Thank you

Don’t forget to join my website too, bro, thank you

Prediksi Hk

Amazing Day!!!

Hello guysss

Morning Computer

Check this out: technology-and-gadget-news

Amazing Day!!!

Hello guysss

Prima Radio

Check this out: technology-news

Amazing Day!!!

Hello guysss

In Finance

Check this out: finance-stories

Howdy very nice website!!

I am satisfied to seek out numerous useful information here in the post, we’d like to develop more strategies in this regard, thank you for sharing. . . . . .

Check out this: games-news

Howdy very nice website!!

I am satisfied to seek out numerous useful information here in the post, we’d like to develop more strategies in this regard, thank you for sharing. . . . . .

Check out this: technology-news

Howdy very nice website!!

I am satisfied to seek out numerous useful information here in the post, we’d like to develop more strategies in this regard, thank you for sharing. . . . . .

Check out this: technology-news

This was a really wonderful post, thanks

Paito Taiwan

This is AWESOME! Great post! Thank you for sharing with us! Please find more useful post at my web!

Click : slot 5000

This is AWESOME! Great post! Thank you for sharing with us! Please find more useful post at my web!

follow me for more info website gacor

makelar33

This was a really wonderful post, thanks

syair china

Erek Erek adalah situs Erek Erek tafsir mimpi togel.

nice post Paito China

prediksi jitu hk

prediksi sgp hari ini

prediksi sdy hari ini

prediksi macau hari ini

prediksi taiwan hari ini

prediksi china hari ini

prediksi cambodia hari ini

prediksi jitu china

I carry on listening to the reports speak about getting free online grant applications so I have been looking around for the most excellent site to get one. Could you advise me please, where could i get some?

Paito SGP

Prediksi Macau

Angka Keramat

Angka Keramat

Live Draw Macau

Live Draw SGP

PREDIKSI DEWA ANGKA

Angka Keramat

Paito Warna SDY

Live Draw SDY

Kocok Live

Kocok HK

Kocok SGP

Kocok SDY

Angka Mistik

Prediktor Angka

Angka Petir

Paito Warna Macau

Toto Togel Terpercaya

BO Togel Terpercaya

Poolstoto togel

Link Poolstoto

https://www.craftberrybush.com/2020/12/christmas-nutcracker-cylinder-wrapping-diy.html

Live Draw SDY

Syair Hk

Syair Sgp

Syair Sdy

Syair Macau

my page Prediksi China

my website Syair HK

my website Syair SGP

my website Syair SDY

Very2 good article guys….

look my website: Data Sdy 2024

Live Draw Sdy

hasil Live Draw Macau

situs Result SDY tercepat

rekap data Paito Warna Hk

keluaran singapore, Data Sgp terlengkap.

nice bro

Prediksi angka hk,sdy,sgp paling jitu di angka profesor

visit my bo poolstoto

visit link my website poolstoto

vsit link Prediksi HK

visit link Prediksi HK

Angka Keramat visit link

Nice post Prediksi Macau

Prediksi Sdy nice post

RUSA4D

Budaya 4D Situs Main Judi Slot Terpercaya Paling Gacor Hari Ini Dengan Game Terbaru Dan Lengkap Hanya Tersedia Di Budaya4D.

yang sedang viral dan sering meledak ledak

official live hk you can visitLIVE DRAW HK HARI INI

Indo6D

my pages paito hk

my pages syair macau

Thanks for sharing this one. Link

Erek erek 2d

kamu nanya ? sini belajar sama kakek DATA SDY

planet4d

Experience the thrill of premium gaming at 24kbet casinogames where a wide variety of casinogames await you.

Experience the thrill of 24kbet casino games and dive into a world of excitement and entertainment like never before.

Are you ready to become the next big winner? At 24kbet, we offer an exciting and diverse platform for all your betting needs. From sports betting and games to slots, lottery, cockfights, fishing, and arcade games, we have something for everyone. Enjoy competitive odds, fantastic bonuses, and a user-friendly experience that makes betting enjoyable and easy. Join 24kwinner today and take your chance at winning big!

Data SDY

Self-regulation refers to the ability to manage and control our emotions, particularly in challenging or stressful situations. This involves techniques such as deep breathing, mindfulness meditation, and reframing negative thoughts, which can help us maintain a sense of calm and perspective.

ipltata casino

apriansyahf371@gmail.com

Join 24kbet today for an exciting and diverse gaming experience with top-notch odds and fantastic bonuses.

MARS 4D mars4d

Exploring the Significance of Title I and Title II in Shaping the Future of Net Neutrality

uefa euro 2024

Title I vs. Title II: Navigating the Debate Surrounding Net Neutrality’s Regulatory Framework

ipl news

venusbet venusbet

Thank you for providing such valuable information. It’s really helpful

tata ipl casino

planet4d planet4d

Paito Sgp, Paito Warna SGP, Paito Sgp Harian ini penting untuk para master merumus dan menemukan pola jitu dalam permainan togel. Data Paito SGP ini akan terupdate otomatis setiap pukul 17:40 WIB.

Website: Paito Warna Sgp

Data sydney, data sdy, Data Pengeluaran Sdy Terbaru, keluaran sdy, result sdy, situs resmi togel sydney terbaru, terlengkap dan terpercaya.

Website: Data Pengeluaran Sdy Terbaru

Result Data Oregon 03:00 Wib(Data Oregon 3), 06:00 Wib(Data Pengeluaran Oregon 6), 09:00 Wib(Oregon 9) dan Pukul 12:00 Wib(Result Oregon 12).

Website: Data Pengeluaran Oregon

uranustoto

I admire your creativity in problem-solving. You bring fresh ideas to the table that inspire us all. Check my page for other related articles ipl 365

mars4d

venusbet

mars4d

Paito Macau

Terima kasih atas ilmu yang Anda bagikan. kunjungi juga website saya RUPIAH89

Artikel yang sangat informatif dan relevan. kunjungi juga website saya CSOWIN

Saya sudah mencari situs yang seperti ini! Pengalaman bermainnya menghibur, dan saya senang dengan sistem pembayaran yang lancar. hanya di BJOPLAY

Saya suka bagaimana Anda menjelaskan semuanya. kunjungi juga website saya SENYUMTOTO

Terima kasih atas artikelnya yang informatif dan menginspirasi! kunjungi juga website saya WD33

I admire your creativity in problem-solving. You bring fresh ideas to the table that inspire us all. Check my page for other related articles ipl365

planet4d

I appreciate the depth of your analysis.If anyone wants to read the topic in more detail then visit porn

Join our blog community, where insightful articles and engaging discussions bring everyone closer together! Connect with like-minded individuals, share your thoughts, and stay updated with the latest trends and topics. Let’s grow and learn together

weltbet….

venusbet

You bring fresh ideas to the table that inspire us all. Check my page for other related articles ipltata sports app review

I admire your creativity in problem-solving. You bring fresh ideas to the table that inspire us all. Check my page for other related articles ipltata sports app login

Check my page for other related articles my11circle login

I admire your creativity in problem-solving. You bring fresh ideas to the table that inspire us all. Check my page for other related articles ipltata

I admire your creativity in problem-solving. You bring fresh ideas to the table that inspire us all. Check my page for other related articles iplt

You bring fresh ideas to the table that inspire us all. Check my page for other related articles ipltata

You bring fresh ideas to the table that inspire us all. Check my page for other related articles iplt

You bring fresh ideas to the table that inspire us all. Check my page for other related articles iplt app

You bring fresh ideas to the table that inspire us all. Check my page for other related articles tata ipl

Where insightful articles and engaging discussions bring us together! Connect with like-minded individuals, share your insights, and stay updated on the latest trends and topics. Let’s grow and learn together!

24kbet register

Agen situs slot Guugle888 resmi yang memiliki visi dan misi selalu memberikan layanan permainan yang terbaik.

mars4d

Sumclub is a bookmaker that provides an online entertainment platform, including betting, slot and casino games. With an easy-to-use interface, Sumclub attracts players thanks to its reputable service and attractive incentives. https://sumclub.bar/

Well done on producing this article! I am grateful for the dedication and investigation that was put into crafting such informative and stimulating content.

Paito Cambodia, Paito Warna Cambodia, Paito Cambodia Harian Terbaru Lengkap.

Data Macau – Data Toto Macau 2025

Toto KL, Toto KL Sore, Toto KL Malam,Pengeluaran Toto Kuda Lari Semarang Hari Ini terlengkap dan terupdate Sore Dan malam.

trusted online casino agent in Asia by providing interesting and live games that you can watch SOBATGAMING

I believe in fostering a positive and respectful environment where everyone voice matters. Feel free to share your thoughts, engage in meaningful discussions, and support one another. Lets create a space that inspires and uplifts!

Paito Cambodia, Paito Warna Cambodia, Paito Magnum Cambodia.

Paito Taiwan, Paito Warna Taiwan, Paito Harian Taiwan.

A very interesting topic that I have been looking at, I think this is one of the most important information for me. And I’m glad to read your post. Thanks for sharing!

uranustoto

Toto KL, Data Toto KL, Pengeluaran Toto KL mencakup keluaran toto KL sore dan pengeluaran toto KL malam tercepat.

Choose the right game and play on the right website, you can try playing on my website, there are many choices of games you can play. Daftar Sobatgaming

uranustoto

It’s really fun, the articles here always have little surprises that make you want to read them for a long time. – latest news of punjab

planet 4d

It’s really fun, the articles here always have little surprises that make you want to read them for a long time. – punjab news in hindi

planet4d

Grewal Transport offers reliable Bangalore To Kochi Truck Transport Services, ensuring the secure and timely delivery of goods. With a well-maintained fleet and skilled drivers, they cater to both businesses and individuals, providing options for full and partial loads. The company prioritizes customer satisfaction with competitive pricing and real-time shipment tracking, making it a leading choice for logistics solutions.

uranustoto

Wow! At last I got a website from where I be capable of

genuinely take useful facts concerning my

study and knowledge.

https://w6.numbersydney.life/

Wow! At last I got a blog from where I can actually get helpful data concerning my

study and knowledge.

https://w3.syairpandawa.life/

Pretty! This was an incredibly wonderful article.

Thank you for providing these details.

https://w2.hongkongdraw.today/

Moving from Mumbai to Ahmedabad becomes much easier with Movers and Packers from Mumbai to ahmedabad. These professionals manage all aspects of your move, including packing, loading, transportation, and unloading. They ensure that your belongings are securely packed and protected during the journey using premium materials. Many services also offer vehicle shipping, temporary storage, and insurance coverage, adding extra convenience. With their experience, you can be sure your move will be handled with care, allowing you to enjoy a smooth and stress-free transition to Ahmedabad.

Paito HK Lotto, Paito Hongkong Lotto, Paito Warna HK Lotto.

Live Draw SGP – Live Result Singapore – Live Singapore Pools

Searching for Property dealers in garhi-harsaru? Our expert team specializes in residential, and commercial. properties. We offer a wide variety of options, ensuring you find the perfect property for your needs. Whether you’re buying, selling, or renting, we provide personalized services, transparent pricing, and expert advice. Let us guide you through every step of the property process in Garhi-Harsaru.

Data SGP 2025 – Data Pengeluaran Singapore 2025

Are you a gambler looking for a source of income through online slot games? สล็อตวอเลท

We also have legal licensed games to invest in slot

such as slot games, which help you generate income safely. สล็อตออนไลน์

nvesting without an agent Come here and play with us. wm787

Meet all needs If you want to play any type of game, there are all types. wm787online

uranustoto

Wow! In the end I got a blog from where I can in fact get useful facts concerning my study and knowledge.

This post really resonates with me! The message is powerful, and I love how you framed it. Great job!

King PH

I’m impressed by the details that you have on this site.You have a good point! I completely agree with what you said!!

Thanks for sharing your views…hopefully more people will check out

Visit us:

Villas for sale in Dubai

Apartments for sale in Dubai1

Apartments for sale in Abudhabi1

Apartments for sale in Sharjah

1

Apartments for sale in Ras Al Khaima1

Apartments for sale in JVC1

Apartments for sale in JVC1

Villas for sale in Abu Dhabi1

Villas for sale in Sharjah1

Scatter78

Thank you for sharing this. It’s really helpful King PH Casino

Data SDY 6D, Data Sydney 6D, Result Togel Sydney 6 Digit, Data Sydney 6D Terlengkap.

Thank you for sharing this. It’s really helpful king casino games ….

Such a stunning shot! You’ve got a great eye for detail. kingph app

Such a stunning shot! You’ve got a great eye for detail. kingph app

..

Such a stunning shot! You’ve got a great eye for detail. kingph app ….

I totally relate to this! I recently experienced something similar and found that mindfulness really helps kinggame

I totally relate to this! I recently experienced something similar and found that mindfulness really helps kinggame

.

mars 4d

Great article! I just read this and really enjoyed it. You may visit kpop porn for more related blogs.

slot online terpercaya

Your attention to detail here is impressive. Well done! kingph casino app

nagasaon It has many helpful functions that users experience.

Data SDY 2025 – Data Pengeluaran Sydney 2025

LIVE DRAW SGP

Paito SGP – Paito Warna SGP – Paito Singapore

Hello. splendid job. I did not expect this. This is a excellent story. Thanks!

I am glad to be a visitor of this unadulterated site! , regards for this rare info ! .

Live Draw SGP – Live Draw Singapore Pools

Hello. splendid job. I did not expect this. This is a excellent story. Thanks!

Perfect piece of work you have done, this web site is really cool with excellent information.

Paito SDY – Paito Harian Sydney – Paito Warna SDY

Wow, I never thought about it that way before! The part where you mentioned your topic really made me think. You’ve got a unique perspective, and I’m here for it. Keep sharing your wisdom! ✨

pisogame

Okay, but how do you make everything look so effortless?! You’ve officially raised the bar for vlogs. 😂 Keep bringing the laughs and good vibes!

crazy buffalo

Live Draw SGP – Live SGP – Live Draw Singapore

very interesting content, thanks for sharing!

Situs Resmi Untuk Login Taruhan Olahraga Online Resmi Terpercaya hanya di BOLA77

Bocoran Sdy

#bocoransdy #syairsdy #togelsdy #prediksisdy #angkajitusdy #angkakerassdy #sydneypools #livekeluaranSDY #togelhariinisdy

This is such an interesting read! It’s always great to discover new perspectives and insights. For those looking for more ways to stay entertained online, check out Lodi646 for an exciting experience!

kunjungin situs togel terpercaya

paito hk lotto

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

I really like your writing style truly loving this site.

I truly appreciate this post. I have been looking all over for this! Thank goodness I found it on social media. You have made my day! Thx again!

Perfect piece of work you have done, this web site is really cool with excellent information.

planet4d

Great read! It’s always refreshing to come across such well-thought-out content. For those who enjoy exciting online experiences, tg 777 is a must-visit!

What a fascinating article! Unique perspectives like this make reading enjoyable. Don’t forget to check out tg 777 for more fun!

This is such an interesting read! It’s always great to discover new perspectives and insights. For those looking for more ways to stay entertained online, check out Lodi646 for an exciting experience!

This was an interesting read, but I would love to see more information on the long-term effects of this approach. You mentioned it’s effective in the short term, but what are the potential drawbacks over time? It would be great if you could dive into that a little more.

casino ranking ph

This is such an eye-opening article! I hadn’t considered that perspective before, and it’s given me a lot to think about. Keep up the amazing work!

jili casino

BATA4D : LINK RESMI BATA4D , LINK LOGIN BATA4D WAJIB GACOR !!!

BATA4D PILIHAN SATU – SATU NYA SITUS TERGACOR , DAFTAR DI BATA4D

Paito Cambodia adalah kumpulan data keluaran angka togel dari pasaran Cambodia yang disajikan dalam bentuk tabel atau grafik. Paito Cambodia

BATA4D : GAMING SLOT ONLINE PALING DI NANTI DI TAHUN 2025

BATA4D : MENCARI KEUNTUNGAN DI BATA4D , LANGSUNG DAFTAR BERSAMA BAT4D.

BATA4D : PILIHAN TERBAIK HANYA DAFTAR DI BATA4D

BATA4D : PLATFORM GAMING ONLINE TERPERCAYA

BATA4D : LINK LOGIN BATA4D PALING GACOR SAAT INI

BATA4D : DAFTAR BATA4D DAN LANGSUNG MAINKAN DI BATA4D

https://fulldocuments.com/

UK driving licence online without exams required. We are your go to people for authentic, original & DVLA verified UK driving licence

situs togel Keluaran Togel Hongkong & Sydney dengan Update Tercepat

Budaya4D adalah platform judi slot resmi yang terpercaya memberikan kemudahan yang tidak boleh anda lewatkan. BUDAYA4D

BATA4D : PLATFORM GAMING ONLINE TERPERCAYA

BATA4D : LINK LOGIN BATA4D PALING GACOR SAAT INI

BATA4D : DAFTAR BATA4D DAN LANGSUNG MAINKAN DI BATA4D

BATA4D : PLATFORM GAMING ONLINE TERPERCAYA !!

BATA4D : LINK LOGIN BATA4D PALING GACOR SAAT INI !!

BATA4D : DAFTAR BATA4D DAN LANGSUNG MAINKAN DI BATA4D !!

I just wanted to say thank you for writing such a comprehensive post! I’ve been trying to learn more about this topic, and your clear explanations and w ell-organized structure made it so much easier to understand. Keep up the great work!

pisogame

BATA4D : PLATFORM QRIS ONLINE DEPOSIT LANCAR 1 DETIK !!!

Get the fastest Checkmate and improve your chess skills as never before!

JITUANGKA PROSES TERCEPAT

JITUANGKA

Paito HK Lotto – Paito Hongkong Lotto – Paito Warna HK Lotto adalah kumpulan data pengeluaran Togel Hongkong yang telah kami susun dalam format tabel. Paito ini akan diperbarui secara otomatis setelah hasil angka dari HongkongLotto.com diumumkan pada pukul 23:00 WIB setiap hari.

Prediksi Macau adalah sesuatu yang sangat banyak dicari oleh para pasukan pecinta togel mania. Hasil Bocoran Angka Jitu Toto Macau 4D 5D yang akurat merupakan tujuan dalam bermain togel. Untuk dapat memenangkan di result togel hari ini. Kombinasi yang baik akan memberikan hasil yang terbaik. Oleh karena itu racik angka sesuka hatimu menurut felling masing-masing.

Ingin tahu rahasia bikin konten yang cepat viral? Yuk pelajari https://aksesviral.site/ cara pakai narasi pendek buat bikin konten meledak di artikel ini!

Postingan ini bermanfaat banget! Saya juga punya ulasan menarik terkait hal ini. SELEBTOTO

Artikel ini sangat informatif. Saya juga nemu situs yang udah support layanan 24 jam, yaitu SBOTOTO. Sangat membantu ketika ada keluhan transaksi. SBOTOTO

Let Powered Now handle your subject trade business paperwork, buyer communications

and scheduling while Xero does your accounts and

payroll.

The course also goals to show participants advanced restore methods for numerous boilers.

Creating job alerts will allow you to maintain up-to-date with the most recent Gas Engineer jobs alternatives.

NusaSuara adalah portal berita dan opini yang menyuarakan realitas masyarakat Indonesia, dari pelosok hingga perkotaan. Fokus pada jurnalisme independen, isu sosial, politik, budaya, dan gaya hidup nusantara.

We enjoy painting and decorating and believe in providing exceptional service for your home

or office.

Artikel ini sangat informatif. Saya juga nemu situs yang udah support layanan 24 jam, yaitu VG78SLOT. Sangat membantu ketika ada keluhan transaksi.

I do believe all of the ideas you have introduced to your post. They’re really convincing and will certainly work. Nonetheless, the posts are too quick for newbies. May you please prolong them a bit from subsequent time? Thanks for the post.

paito china menyajikan data historis yang lengkap, akurat

Perfect piece of work you have done, this web site is really cool with excellent information.

We operate from Thanet to Canterbury and surrounding

towns and villages areas.

venusbet >> menghadirkan beragam pilihan game slot dengan kualitas grafik tinggi serta fitur menarik.

Many problems can occur with gas and electricity

supplies at home.

Setiap paragrafnya mengandung insight yang bermanfaat banget.

Buat yang baru belajar topik ini, artikel ini wajib dibaca. http://www.realdolldoctor.com

Salut dengan cara penulis menyampaikan informasi yang padat dan jelas.

Saya menemukan banyak informasi baru yang sebelumnya saya belum tahu. (variasi)

Salah satu tulisan paling berbobot yang saya baca hari ini. (variasi)

Setuju banget dengan poin-poin yang disampaikan penulis.

Tiap kali berkunjung ke situs ini, saya selalu dapat ilmu baru.

Bahasannya lengkap dan berimbang, benar-benar bikin tambah wawasan.

Saya menemukan banyak informasi baru yang sebelumnya saya belum tahu.

Informasinya daging semua, saya jadi lebih paham setelah baca artikel ini.

Artikel ini sangat berguna untuk saya, terutama di bidang yang sedang saya pelajari.

Ternyata masih banyak yang bisa dipelajari dari artikel seperti ini, keren!

Salah satu tulisan paling berbobot yang saya baca hari ini. (variasi)

Gaya penulisannya menarik, bikin betah baca sampai akhir.

Tulisannya ringan tapi tetap berisi, cocok buat segala kalangan.

Sudut pandangnya unik dan jarang dibahas, makasih sudah mengangkat topik ini.

Salah satu tulisan paling berbobot yang saya baca hari ini.

Makin banyak tulisan seperti ini, makin maju juga pembacanya.

Saya merasa relate banget sama isi artikelnya, mantap.

Pembahasannya up-to-date dan mengikuti isu yang sedang tren.

Saya menemukan banyak informasi baru yang sebelumnya saya belum tahu. (variasi) (variasi)

Tiap kali berkunjung ke situs ini, saya selalu dapat ilmu baru. (variasi)

Saya menemukan banyak informasi baru yang sebelumnya saya belum tahu. (variasi)

Sungguh ulasan yang berkualitas, senang bisa menemukan bacaan seperti ini.

Terima kasih sudah menulis sesuatu yang sangat bermakna.

Tulisannya sangat menginspirasi, semoga makin banyak konten seperti ini ke depannya. (variasi)

Terima kasih sudah menulis sesuatu yang sangat bermakna. (variasi)

Artikel ini bikin saya penasaran untuk belajar lebih jauh lagi.

Sudut pandangnya unik dan jarang dibahas, makasih sudah mengangkat topik ini. (variasi)

Sangat cocok untuk pembaca yang mencari referensi terpercaya.

Kontennya menarik dan membuka wawasan baru, terima kasih sudah berbagi.

Tulisannya sangat menginspirasi, semoga makin banyak konten seperti ini ke depannya.

Tulisan ini memberikan perspektif berbeda yang layak dipertimbangkan.

Bahasannya runut dan mudah diikuti, nggak bikin bingung.

Pemaparan fakta dan opini disusun dengan sangat profesional.

Penjelasan yang rinci dan mudah dipahami, cocok buat pemula juga.

This time, they managed to arrange for a boiler service the next day, which really helped me

out.

Paito Taiwan merupakan salah satu acuan utama bagi para penggemar angka dalam menganalisis data keluaran dari pasaran Taiwan.

Standalone app. There are tons of different URL shortening choices out

there, and i restricted my search to easy-to-set-up, standalone services.

It is more complex to implement as we have to handle the batch of IDs and ensure that we do not run out and should generate more IDs when the batch is exhausted.

Analysis and academic content material URLs typically run lengthy, prompting the increasing use

of short URLs. However it’s an more and more poor choice for small companies and particular person users who wish

to generate short URLs and comply with their stats for

a modest variety of campaigns. Predictability: Incremental IDs are predictable, which

implies that someone may doubtlessly infer the variety of URLs shortened by

your service or guess different users’ URLs by merely incrementing

the quick URL. For instance, if the brief url is a82c7w, the request handler would go to shard a to find the lengthy url.

ID for every new URL as requests come in and reserve it to the database.

Background Jobs: A background job or cron job can be scheduled to periodically test

for expired URLs and mark them as inactive or delete them from the database.

Salah satu tulisan paling berbobot yang saya baca hari ini.

Tulisan ini memberikan perspektif berbeda yang layak dipertimbangkan.

aya menemukan banyak informasi baru yang sebelumnya saya belum tahu.

Live Draw Sydney kami menayangkan hasil secara langsung dari sumber resmi.

Paito HK Lotto – salah satu alat analisis terbaru dan dapat dipercayai untuk belajar memprediksi angka jitu keluaran togel HK Lotto.

visit Paito Hk Lotto

visit Paito Warna Sgp

Data SDY Lotto thanks you

WD33 Link No 1 Game Slot & APK Paling Gacor 100%

3PRIZETOTO

Great post! I’ve been exploring Jilibets Fun lately and it’s been awesome: https://jilibets.fun/

It keep a amazing blog.

Very nice

the quality of your sleep play vital roles in your overall well-being.

“This was such a helpful and enjoyable read! I really appreciate the time and effort that went into putting this together. It’s clear, easy to follow, and full of useful details. Definitely bookmarking this to come back to again. Thanks for sharing!

Data SDY yes

Lodi 291 app is a popular online casino app in the Philippines that provides players with access to slot games, live casino tables, sports betting, and more.

Lodi 291 app is a popular online casino app in the Philippines that provides players with access to slot games, live casino tables, sports betting, and more.

The part about using Moviebox with Chromecast was really useful. I never realized how easy it is to stream directly to my TV. Now I can enjoy movies on the big screen without any lag.

If you’re into podcasts as much as music, Spotify is perfect. I can listen to my favorite podcasts, save episodes, and even get recommendations based on my listening habits. It feels like everything I need for audio entertainment in one app.

VEGASTOGEL

Discover how to quickly set up your Canon printer with https ij start canon. Follow step-by-step instructions to install drivers, connect to Wi-Fi, and start printing effortlessly.

Discover how to access your Lorex Home Login to view live camera feeds, manage security settings, and control devices remotely for a safer and smarter home experience.

This recently came across my radar, and I found it to be a well-articulated and insightful read. I figured it was worth passing along.

INDO6D sarapan pagi dengan uang tambahan, cara dapat gampang cukup ikut arahan dari kami di jamin pasti ada uang saku tambahan bisa bawa keluarga jalan-jalan.

MEXQuick is your gateway to smart trading with Event Contracts, Rhythm Contracts, and Forex. Learn, practice, and succeed with powerful tools, expert insights, and a secure platform designed for traders at every level.

Discover Morocco Classic Tours with Travel Experts offering customizable journeys from imperial cities to luxury desert camps across this beautiful country.

Paito HK Lotto thanks

Platform Gaming Online Terpercaya Server Thailand BARCELONA88

Great insights on how RTP affects online slot outcomes! I’ve found that choosing a trusted platform with transparent payout rates makes a huge difference in player experience. Thanks for sharing these tips!

This is a really interesting look at net neutrality! It’s crazy how much the regulations have changed over the years. Makes you wonder what’s really going to happen with UMA Racing Codes and everything else online in the future. 🤔

SHBET Nhà cái uy tín 2025, được cấp phép hợp pháp bởi Isle of Man & Cagayan. Trải nghiệm thể thao, bắn cá, đá gà, slot game đẳng cấp quốc tế.

SHBET – sân chơi cá cược uy tín, nạp rút nhanh, tỷ lệ cao giúp người chơi thăng hoa mỗi ngày.

F168 là lựa chọn hoàn hảo cho thế hệ cá cược mới. Bảo mật tiên tiến, nạp rút nhanh như chớp, kho trò chơi khổng lồ (thể thao, đá gà, xổ số,…) – “đã” từng khoảnh khắc.

https://f168.vision/ là nền tảng giải trí trực tuyến uy tín hàng đầu hiện nay, nổi bật với tốc độ truy cập cực nhanh, hệ thống bảo mật đa lớp và giao diện tối ưu cho mọi thiết bị.

Thanks, this was very enlightening.

Great post! I really enjoyed reading this and found the information helpful.

EEJL – new technology betting platform, transparent, diverse games for players.

hm88pink tăng hiệu quả xử lý đa nhiệm, giúp người Việt thao tác không gián đoạn.

88CLB – sân chơi cá cược uy tín, tốc độ và minh bạch, mang đến trải nghiệm giải trí đỉnh cao cho người chơi.

JILI7 is a modern online entertainment platform that offers users a diverse and smooth experience. With an optimized interface and a stable operating system, aims to provide convenience, safety, and reliability in every entertainment activity.

https://99okbio.eu.com/

tự hào là nơi giới tinh hoa không cần tìm thêm đâu nữa, vì đã có tất cả những gì tinh túy nhất ở đây.

KJC được biết đến như một tổ chức quốc tế định hướng phát triển ngành giải trí trực tuyến hiện đại.

https://68winclub.co.com/

đẩy nhanh hiệu suất xử lý, giúp người dùng truy cập online ổn định hơn.

F168 là nền tảng cung cấp dịch vụ cá cược trực tuyến; người dùng cần tuân thủ quy định pháp lý khi truy cập.

SM66 – chơi dễ thắng lớn, môi trường công bằng, dịch vụ chuyên nghiệp.

VMAX – nền tảng cá cược uy tín, giao diện mượt và tỷ lệ thưởng cao, được người chơi tin chọn mỗi ngày.

GOOD INFORMATION!!!

89bet green là một trong những thương hiệu giải trí trực tuyến lâu đời, khởi đầu từ năm 2000 và phát triển mạnh mẽ suốt hơn 20 năm hoạt động.

GK88 nâng cao hiệu năng hiển thị, hỗ trợ người dùng trải nghiệm web mượt mà.

GG88 Cung cấp nhiều lựa chọn cá cược đa dạng, từ các môn thể thao phổ biến đến những sự kiện đặc biệt, giúp người chơi thoải mái chọn lựa.Hệ thống thanh toán nhanh chóng và hỗ trợ khách hàng 24/7 sẽ mang đến trải nghiệm trọn vẹn và an tâm cho mọi người tham gia.

89BET mang đến sân chơi giải trí uy tín, bảo mật cao, nạp rút nhanh và hỗ trợ người chơi 24/7.

Thanks for every other informative site.

lunabet menghadirkan berbagai pilihan permainan modern yang terus diperbarui agar pemain mendapatkan pengalaman terbaik Dengan layanan yang konsisten.

This article helps readers gain confidence

sc8844 com là nền tảng giải trí cho người chơi yêu sự khác biệt.

This is a great, well-rounded list of destinations with clear and warm water. I like how it highlights spots from different regions, making it useful for many types of travelers.

Sepuh cheat merupakan sebuah situs di interntet yang menyediakan ruang diskusi dan interaksi para kalangan gamer pemain lama atau biasa disebut gamer sepuh.

For a research subject , you’ll want an essay guy who has experience with research paper writing.

https://vmaxgame.net/ ra mắt đánh dấu bước khởi đầu ấn tượng trong ngành giải trí trực tuyến. Chỉ sau vài năm, nền tảng đã nhanh chóng thu hút đông đảo người chơi, tạo dựng uy tín nhờ hệ thống game đa dạng và dịch vụ chất lượng cao

For a research subject , you’ll want an essay guy who has experience with research paper writing.

This is a great, well-rounded list of destinations with clear and warm water. I like how it highlights spots from different regions, making it useful for many types of travelers.

This website QiuQiu99 consistently shows credibility through secure systems, fast performance, clear content, and professional management, making it a genuinely trusted and highly recommended platform for online users worldwide today.

I used to stress over every assignment until I realized you can simply buy essay online from reliable writers. It’s not about cheating—it’s about managing time.

KJC không chỉ là một tập đoàn giải trí hàng đầu mà còn là biểu tượng của sự đột phá trong thế giới game trực tuyến.

Kjc liên minh tập trung vào việc kết hợp công nghệ tiên tiến với quản trị chuyên nghiệp, tạo nên một nền tảng giải trí trực tuyến ổn định, minh bạch và an toàn.

https://thabet.cx/ Nhờ tuân thủ pháp luật quốc tế, tiêu chuẩn của các tổ chức này, nhà cái đã được xếp hạng vào những sân chơi hợp pháp tiêu biểu nhất châu Á năm 2025

F8bet.me

từng bước xây dựng hình ảnh chuyên nghiệp thông qua việc đầu tư vào hệ thống kỹ thuật, góp phần mang lại môi trường trực tuyến ổn định, thuận tiện và phù hợp với nhu cầu người dùng hiện đại.

kjc liên minh là nền tảng giải trí trực tuyến hiện đại, mang đến không gian trải nghiệm đa dạng và thân thiện cho người dùng. Với giao diện trực quan và công nghệ ổn định, hướng đến sự tiện lợi và an toàn trong mọi hoạt động giải trí.

Paito Sdy

Nhờ chiến lược phát triển bài bản, Link F8bet ngày càng mở rộng cộng đồng người dùng.

Thanks again for sharing this travel inspiration.

Thank you for providing such excellent information. Your website has a clean, professional feel, and I truly appreciate the depth of knowledge shared here.

Great Post !!! Paito SDY

i liked the article it was very great and good

Nhà cái thabet mang đến trải nghiệm cá cược an toàn và minh bạch cho người chơi. Hỗ trợ 24/7 cùng nhiều ưu đãi hấp dẫn.

XX88 – Sân chơi giải trí trực tuyến uy tín, giao diện mượt mà. Nạp rút nhanh, ưu đãi hấp dẫn mỗi ngày.

MM 88 mang đến trải nghiệm cá cược an toàn, minh bạch cùng tỷ lệ kèo cạnh tranh. Hệ thống hiện đại, hỗ trợ 24/7, thanh toán nhanh chóng, phù hợp cho cả người mới lẫn cao thủ.

Very nice and informative content. It’s always good to come across posts that are clear, engaging, and useful at the same time.

MM88 mang đến môi trường cá cược chuyên nghiệp, an toàn tuyệt đối cùng hệ thống hỗ trợ nhanh chóng, giúp người chơi yên tâm trải nghiệm mọi lúc.

Thanks for this article. I can find a lot of good answers.

MM88 khẳng định uy tín trong lĩnh vực cá cược trực tuyến với kho game phong phú, kèo cược chuẩn, thanh toán nhanh gọn và chính sách bảo mật nghiêm ngặt cho người chơi.

Great blog! The information is clearly explained and well organized

LLwin giúp người chơi trải nghiệm cá cược mượt mà. Rút tiền trong 30s mang lại sự tiện lợi.

nice post and please check web

sc88.charity được thiết kế nhằm tối ưu trải nghiệm người dùng. Giao diện trực quan giúp quá trình sử dụng không gặp nhiều trở ngại.

Bin88 – điểm đến lý tưởng cho cược thủ yêu thích cá cược online. Đăng ký nhanh, chơi mượt, thưởng lớn, bảo mật thông tin và thanh toán an toàn tuyệt đối.

Bin88 được phát triển theo định hướng trải nghiệm người dùng, mang đến môi trường giải trí trực tuyến hiện đại, ổn định và đáng tin cậy.

This is a very informative and well-written article.

Your perspective is so unique; I always learn something new here.

Thank you for sharing such high-quality content.

What a data of un-ambiguity and preserveness of precious know-how on the topic of

unexpected feelings.

Thanks for this post. You shared amazing article with us.

Jun 888 gây ấn tượng nhờ cách bố trí khoa học, màu sắc dễ nhìn cùng các danh mục trò chơi rõ ràng, giúp người chơi tiết kiệm thời gian khi tìm kiếm và tham gia giải trí.

This really gave me a lot to think about.

A very thought-provoking perspective on [tokek toto]

I’ve never looked at it this way before. Thanks for the fresh take!tokek toto

This was a very informative read. I learned so much!

This type of is apparently absolutely outstanding. These kinds of tiny fact is made making use of wide variety regarding certification know-how.

Really interesting post! I always enjoy reading content that is clear and informative like this.

I always struggled with deadlines until I discovered this site.

This is such an insightful piece.

The Cupidbaba vibrators features a refined design built for ease and reliability. Gentle vibration patterns help users unwind, while the balanced structure ensures comfortable use. Designed with safety and discretion in mind, it fits naturally into calm, private wellness moments.

Spot on! You nailed it.tokek toto

Spot on! You nailed it .This provided such a fresh perspective on the topic.tokek toto

bolaqiuqiu is a list of login links for the 2026 World Cup soccer betting site.

tokektoto tokektoto

tokek toto tokek toto

tokektoto tokektoto 1

read this blog further, it’s very exciting